Framework for the Incarceration of Foreign Nationals

With an increase in international travel and migration, the number of imprisoned foreign citizens has also gone up. Some countries deport or otherwise immediately remove all foreign nationals who are sentenced, while others continue to prosecute and punish with lengthy terms of imprisonment. In some other countries, persons can be convicted of and imprisoned for immigration related offences, alongside prisoners who have been convicted of criminal offences.

Even though FNPs(Foreign national Prisoners) constitute a small part of prison population now, their numbers are likely to rise. This can add pressure on the resources of prison authorities, unless criminal policies are rationalized and adequate investment is made to address the challenges related to supervision, care and protection of prisoners with special needs. Thus, it is imperative to first understand the existing framework under both international and national law for the confinement of foreign nationals in prisons in India.

Framework under international instruments and conventions

The Standard Minimum Rules, Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under any form of Detention or Imprisonment, Vienna Convention on Consular Relations9, United Nations Convention Against Torture, Model Agreement on the Transfer of Foreign Prisoners and Recommendations for the Treatment of Foreign Prisoners, etc. guide the confinement and treatment of foreign nationals while in prison. Broadly speaking, in addition to all other guarantees and protections provided to all prisoners, foreign nationals are also entitled to the following rights:

i. Right of information regarding arrest or apprehension to consular post:

This is one of the most important rights that must be guaranteed at the time of a foreigner’s arrest. This entails the immediate communication of information about the apprehension to the citizen’s diplomatic mission in the arresting country. Article 36(b) of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations 1963 (The Convention) states that the competent authorities should inform the consular post of the concerned state, ‘if, within its consular district, a national of that State is arrested or committed to prison or to custody pending trial or is detained in any

other manner’. This right can also be found under the Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment. Principle 16 states that, ‘If a detained or imprisoned person is a foreigner, he shall also be promptly informed of his right to communicate by appropriate means with a consular post or the diplomatic mission of the State of which he is a national or which is otherwise entitled to receive such communication in accordance with international law or with the representative of the competent international organization, if he is a refugee or is otherwise under the protection of an Inter governmental organization.’ The United Nations Convention Against Torture also contains similar provisions.

ii. Right to communicate with their diplomatic mission and consular access:

Irrespective of the arrest or detention of any person, all foreigners are entitled to this right. In case of detention, however Article 36(b) of the Convention also ensures that ‘any communication addressed to the consular post by the person arrested, in prison, custody or detention shall be forwarded by the said authorities without delay.’Rule 62 of the Nelson Mandela Rules 2015 also entails that ‘prisoners who are foreign nationals shall be allowed reasonable facilities to communicate with the diplomatic and consular representatives of the State to which they belong.’

iii. Right to be visited by consular officers in place of detention:

Article 36(c) of the Convention further provides that consular officers shall have the right to visit their national who is in prison, custody or detention within their jurisdiction, to converse and correspond with him and to arrange for his legal representation. These authorities are also required to inform the person concerned without delay of his rights.

iv. Right of prisoners to refuse visit or communication with consular officers:

Foreign nationals have a right to refuse consular access as well. Article 36 (c) states that ‘nevertheless, consular officers shall refrain from taking action on behalf of a national who is in prison, custody or detention if he expressly opposes such action.’

v. Right to Communicate with their families and friends:

Detention can be a very traumatic experience for anyone, thus staying in touch with their families and the realities of the outside world is very important. Rule 37 of the Nelson Mandela Rules states that ‘Prisoners shall be allowed under necessary supervision to communicate with their family and reputable friends at regular intervals, both by correspondence and by receiving visits.’ This applies equally for foreigners as well.

vi. Right to communicate in language understood by him/her :

An arrested person has a right to know the offence they have been charged with, but more importantly if the arrested person and the arresting authority do not speak the same language, a translator shall be provided and a translated copy of the charge-sheet shall also be provided, so that one may be able to defend themselves adequately. Article 14 of the Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment, states that ‘a person who does not adequately understand or speak the language used by the authorities responsible for his arrest, detention or imprisonment is entitled to receive promptly in a language which he understands the information referred to…and to have the assistance, free of charge, if necessary, of an interpreter in connection with legal proceedings subsequent to his arrest.’

vii. Right to seek transfer to home country for serving remaining part of sentence:

In 1985, the Seventh UN Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of offenders adopted the UN Model Agreement on the Transfer of Foreign Prisoners and Recommendations on the treatment of foreign prisoners (see box below). This agreement provides a model not only for bilateral agreements but also for multilateral agreements that all UN Member States can adapt to their specific legal systems. Several international instruments are also relevant to the international transfer of sentenced persons, including those referring to rehabilitation and human rights of prisoners. Among them is the United Nations Transnational Organized Crime Convention, which states, in Article 17, that: “States Parties may consider entering into bilateral or multilateral agreements or arrangements on the transfer to their territory of persons sentenced to imprisonment or other forms of deprivation of liberty for offences covered by this Convention, in order that they may complete their sentences there.”

Recommendations for the treatment of foreign prisoners

- The allocation of a foreign prisoner to a prison establishment should not be effected on the grounds of his nationality alone.

- Foreign prisoners should have the same access as national prisoners to education, work and vocational training.

- Foreign prisoners should be eligible for measures alternative to imprisonment, as well as for prison leave and other authorised exits from prison according to the same principle as nationals.

- Foreign prisoners should be informed promptly after reception into a prison, in a language which they understand and generally in writing, of the main features of the prison regime, including relevant rules and regulations.

- The religious precepts and customs of foreign prisoners should be respected, with reference, above all, to food and working hours.

- Foreign prisoners should be informed without delay of their right to request contacts with their consular authorities, as well as of any other relevant information regarding their status. If a foreign prisoner wishes to receive assistance from a diplomatic or consular authority, the latter should be contacted promptly.

- Foreign prisoners should be given proper assistance, in a language they can understand, when dealing with medical or programme staff and in such matters as complaints, special accommodations, special diets and religious representation and counselling.

- Contacts of foreign prisoners with families and community agencies should be facilitated, by providing all necessary opportunities for visits and correspondence, with the consent of the prisoner. Humanitarian international organizations, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross, should be given the opportunity to assist foreign prisoners.

- The conclusions of bilateral and multilateral agreements on supervision of and assistance to offenders given suspended sentences or granted parole could further contribute to the solution of the problem faced by foreign offenders.

Framework in India

i) Relevant legislations:

The entry, stay, and removal of foreigners in India is governed by the Foreigners Act 1946, the Passport (Entry into India) Act 1920, the Foreigners Order 1948, the Foreigner (Tribunals) Order 1964, the Citizenship Act 1955, the Citizenship (Registration of Citizen & Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003, the Citizenship Rules, 2009, Foreigner’s Tribunal and Illegal Migrants (Determination Tribunals) 1979 and the Repatriation of Prisoners Act 2003.

The Foreigners Act, 1946 confers upon the central government certain powers in respect of the entry of foreigners into India, their presence therein and their departure therefrom. It also contains provisions that prescribe penalties for contravention of provisions. Section 3 of this Act empowers the Central Government by order, to make provisions either generally or with respect to all foreigners, or with respect to any particular foreigner or any prescribed class or description of foreigners, for prohibiting, regulating or restricting their entry into India or their departure there from or their presence or continued presence therein.

The term ‘foreigner is defined in Section 2(a) of the Foreigners Act 1946, to mean a person who is not a citizen of India. The regulations regarding recognition of citizenship are contained in the Citizenship Act, 1955, that was enacted in accordance with powers vested in the parliament by Article 11 of the Constitution of India 1950. The Citizenship Act contains provisions for acquisition and termination of citizenship.

As per the Act there are five modes of acquiring the citizenship of India: by birth, descent, registration, naturalization, incorporation of territory. The act also defines an illegal migrant as a foreigner who entered India

- Without a valid passport or other prescribed travel documents or

- With a valid passport or other

prescribed travel documents but remains in India beyond the permitted period of time.

The Foreigners Order, 1948 further provides for detailed provisions on grant or refusal of permission to enter India and the various restrictions that can be imposed on foreigners. Importantly, section 14 provides for the expenses of deportation. It states that, ‘where an order is made in the case of any foreigner directing, that she shall not remain in India or where a foreigner refused permission to enter India or has entered India without permission, the Central Government may, if it thinks fit, apply any money or property of the foreigner in payment of whole or any part of the expenses of or incidental to the voyage from India and the maintenance until departure of the foreigner and his dependents.’

Further the Passport (Entry into India) Act 1920 empowers the central government to make rules requiring all persons entering India to be in possession of passports, and for all matters ancillary or incidental to that. It also provides for powers to arrest and detain, as well as the power of removal.

ii) Implementing authority:

The implementation of the provisions laid down under the various acts have been enshrined upon the Bureau of Immigration (BoI), set up by the Government of India in the Ministry of Home Affairs, New Delhi. BoI is headed by the Commissioner of Immigration and assisted by Foreigner Regional Registration Offices (FRRO) for immigration facilitation services at airports and work relating to registration of foreigners under various Acts and Rules.

At present, there are 12 FRROs in major cities i.e. Delhi, Mumbai Kolkata, Chennai, Amritsar, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Calicut, Kochi, Trivandrum, Lucknow and Ahmedabad. Apart from this, there are 12 Chief Immigration Officers in the cities i.e. Goa, Jaipur, Gaya, Varanasi, Nagpur, Pune, Mangalore, Trichy, Coimbatore, Bagdogra, Chandigarh and Guwahati. At remaining places District Superintendent of Police (SP) or the prescribed authority functions as FRO to facilitate foreigners.

The functions of the Bureau are:

- Maintenance of all records in respect of every foreigner from the time of grant of a visa to the time of his departure from India;

- Maintenance of up-to-date and complete statistics in respect of all foreigners in India;

- Maintenance of records of movements of all foreigners visiting India;

- Coordination of the work of all Registration Officers;

- Taking steps to ensure that foreigners leave India within the authorized periods of their stay; and

- When a foreigner leaves India by a port or place of entry other than the one through which he enters, intimation regarding such departure will be sent by the Central Foreigners Bureau to the Registration Officer of the port of place of entry.

iii) Penalties :

Foreigners who have contravened any of the provisions given under these legislations can be subjected to certain penalties, including imprisonment. The penalties are found under the specific acts, a list of which is given in Table:

| Section | Offence | Punishement |

| Section 14, Foreigners Act 1946 | Overstays his visa period violates conditions of his visa contravenes any provisions of the Act | Imprisonment which may extend to five years and fine. |

| Section 14 A, Foreigners Act 1946 | Entry into restricted areas without proper permit Enters into or stays in any area in India without the valid documents required | Imprisonmen t for a term which shall not be less than two years, but may extend to eight years and fine which shall not be less than ten thousand rupees but may extend to fifty thousand rupees |

| Section 14B, Foreigners Act 1946 | Using forged passport to enter India | Imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than two years, but may extend to eight years and fine which shall not be less than ten thousand rupees but may extend to fifty thousand rupees. |

| Section 14C, Foreigners Act 1946 | Abetment of any offence punishable under the Act | To be punished with punishment provided for the offence |

| Rule 5, The Repatriation of Prisoners Rules, 2004 |

Escapes custody within India. (After being transferred from a foreign country.) |

The prisoner so arrested shall be liable for committing an offence under section 224 of the Indian Penal Code and shall also be liable for such sentence of imprisonment in India which he would have to undergo if the delivery of custody of such prisoner had not been made under section 8 of The Repatriation of Prisoners Act, 2003. |

| Section 25, The Illegal Migrants(Determination by Tribunals)Act, 1983.Section 25, The |

Contraveningor abetting to contravene an order made under section 20 (expulsion of illegal migrant) of this act. Failure to comply with any directions given by such order. Harbouring a person who has contravened an order under section 20 or failed to comply with directionsnlaid down in such order. |

Shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than one year but which may extend to three years and with fine which shall not be less than two thousand rupees. The court may, for adequate and special reasons to be mentioned in the judgment, impose a sentence of imprisonment for a term of less than one year or a fine of less than two thousand rupees. |

| Section 17, The Citizenship Act,1955 |

Any person who, for the purpose of procuring anything to be done or not to be done under this Act, knowingly makes any representation which is false in a material particular shall be punishable. |

Imprisonment for a term which may extend to [five years], or [with fine which may extend to fifty thousand rupees], or with both. |

| Section 28, The Citizenship Rules, 2009 | Where an order has been made depriving a person registered or naturalised in India of his citizenship of India, the person so deprived or any other person in possession of the certificate of registration or naturalisation shall, when required by notice in writing given by the Central | Non- compliance to the same can make one liable to a fine, which may extend to one thousand rupees. |

| Government, deliver the said certificate to such person and within such period as may be specified in the notice | ||

| Rule 6, The Passport (Entry into India) Rules, 1950 |

Contravention or abetment to contravention of entering India without a valid passport and from an invalid port |

Punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to five years, or with fine which may extend to fifty thousand rupees, or with both |

iv) Adjudication:

Cases filed against FNPs are usually adjudicated by criminal courts as per the provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure 1973. However, in some states, cases pertaining to nationality of Individuals are adjudicated by Foreigner Tribunals. There are, at present a 100 such tribunals set up in Assam. They have been conferred powers of the Civil Court under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 in respect of summoning and enforcing the attendance of any person and examining on oath; requiring the discovery and production of any document; and issuing commissions for examination of any witness.

v) Detention:

Foreign nationals charged and convicted of criminal offences are required to serve their sentence in a prison. Those who have completed their sentences are then required to be formally released from prisons and can be kept in appropriate places with restricted movement pending their Deportation/repatriation. Section 3(2)(e) of the Foreigners Act 1946 empowers the central government to issue orders requiring foreigners to reside in a particular place and impose restrictions on his/her movement. These powers have been delegated to certain state governments in 1958.In 1998, the Ministry of Home Affairs sent a letter suggesting, to the state governments/UT administrators who were delegated powers under section 3(2)(e) of the Foreigners Act 1946, that they may exercise these powers to restrict the movement of foreign nationals awaiting deportation after completion of the sentence pending confirmation of their nationality. It also said therein that the movement of

such foreign nationals should be restricted in one of the detention centres/camps of foreigners to ensure their physical availability at all times for expeditious repatriation/deportation as soon as travel documents are ready.

The power to confine foreign prisoners to detention centres has also been affirmed by the Supreme Court of India in Bhim Singh vs Union of India and others, wherein the court stated,

“Whatever may be the reason for delay in confirmation of their nationality, we have not even slightest doubt that their Continued imprisonment is uncalled for…It is true that unless their nationality is confirmed, they cannot be repatriated and have to be kept in India but until then, they cannot be confined to prison and deprived of basic human rights and human dignity”.

vi) Deportation/Repatriation:

Once a person completes his sentence he must be released from prison. However, in the absence of requisite documents permitting their stay in India, as was explained above, FNPs are usually not released from prison upon completion of their sentences. Instead, they continue to remain in detention, either in a prison or a detention centre, till their repatriation cannot be completed.

Arrest of foreign nationals

A foreign national can be arrested if he is found to be in violation of any rule or order made under any law regulating his stay in India or for the commission of a criminal act during his stay in the country. The Central government has been authorised to pass orders for the arrest and detention of foreign nationals under section 3(2)(g) of the Foreigners Act 1946, for ‘prohibiting regulating or restricting the entry of foreigners into India or their departure therefrom or their presence or continued presence therein’. The power to arrest can also be found in section 4 of the Passport (Entry into India) Act 1920.

Barriers to Justice

Barrier I: Lack of intimation to Consulate/Diplomatic Mission at arrest- Obligation on police to inform consulate:

Very few state police manuals contain provisions that obligate the police to inform the concerned embassy of the arrest of their national, so as to ensure prompt consular access. The Model Police Manual prepared by the Bureau of Police Research and Development, Ministry of Home Affairs42 contains an entire chapter on foreigners. Rule 565 provides that, ‘when foreign nationals are arrested on major criminal or civil charges, it is possible that the Foreign Diplomatic/Consular Missions in India may wish to assist the nationals of their countries in regard to their defence before a court of law and/or take such other action, as they may deem appropriate in accordance with diplomatic practice.

Therefore, as soon as a foreign national (including Pakista national) is arrested in a major crime, the fact, with a brief description of the offence should be brought to the notice of the Ministry of External Affairs through the State Government by the DGP/CP concerned. Government of India, who decides about the necessary action, should bring these cases to the notice of the Foreign Diplomatic/Consular missions concerned. The report of the arrest of a foreign national in a major crime, together with a brief description of the offence, should be communicated to the Director General of Police, Addl. DGP, CID and Addl.DGP Intelligence and Security’.

While not all states have adopted the model manual, police manuals of Andhra Pradesh and Sikkim reproduce

these provisions verbatim. The Mizoram Police Manual also provides that 1111. (b). In the case of foreigners,

interrogators should be conversant with the political complexions, customs and traditions of the country of the person interrogated.

He must have a good grasp of the regulations applicable to foreigners and be aware generally of the activities of foreigners in India.

Barrier II: Lack of nationality verification process at the time of trial:

A peculiar aspect regarding the adjudication of claims of nationality lies in the reversal of the principle of burden of proof, wherein the individual — and not the state — is required to prove the nationality of the individual. This is provided under Section 9 of the Foreigners Act 1946, which states that, ‘whether any person is or is not a foreigner or is or is not a foreigner of a particular class or description

the onus of proving that such person is not a foreigner or is not a foreigner of such particular class or description, as the case may be, shall notwithstanding anything contained in the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 (1 of 1872), lie

upon such person.’

This reversal of the burden of proof is unduly onerous for the prisoner. From a legal perspective, the reversal, while permissible, is an exception to the norm that it must be the prosecuting authorities who prove an allegation against the accused. Where such reversal can be justified on the basis that the accused possesses the best information to prove the material fact, it should be accompanied by procedural safeguards to ensure due process and fairness. However, there are very few, if any, checks and balances to the authorities’ wide powers to determine nationality under the relevant acts. A determination of nationality by the authorities is typically conclusive, leaving very little room for rebuttal by the accused.

This reversal of burden of proof also means that there is no onus on the prosecution to verify the actual nationality of the accused. Thus, once convicted, a foreign national is merely a non-Indian, and no efforts may be taken to verify his true nationality. This poses endless difficulties in ensuring consular access, later leading to delays at the time of repatriation, and in some cases, even leading to indefinite detention, as their only next of kin (the embassy) stays completely unaware of their presence in the country.

Barrier III: Lack of consular access while in prison

Obligation to facilitate consular access

Some prison manuals contain provisions that ensure that whenever a foreign national is admitted, intimation be sent to the chief of prisons. For instance, Rule 8.23 of the Model Prison Manual prepared by the Bureau of Police Research and Development55 states that ‘if any foreign national is committed to prison, or to custody pending trial, or is detained in any other manner, the Superintendent of Prison shall, immediately inform the Inspector General of Prisons. Any communication addressed to a Consulate, by a prisoner or detenue, shall be forwarded to the Ministry of External Affairs through proper channel without undue delay. Such communication shall be subject to scrutiny/ censorship as per rules. The particulars of incoming and outgoing letters of a foreign national, if found objectionable shall be censored and also furnished to the government.’

It further goes on to say in Rule 8.24 that ‘whenever Consulate Officials of a foreign country seek permission to visit or interview a prisoner for arranging legal representation for them, or for any other purpose, the Superintendent of Prison shall inform the Government of such request from the Consulate. Only on receipt of orders from the government the Superintendent of Prison shall permit Consulate officials to visit the prisoner.’

Barrier IV: Lack of contact with family and friends

Obligation to ensure contact with family

The importance of maintaining contact with family for prisoners is well established. In Francis Coraille Mullin vs. The Administrator, Union Territory of Delhi, the Supreme Court of India had categorically said, “As part of the right to live with human dignity and therefore, as a necessary component of the right to life, he would be entitled to have interviews with the members of his family and friends and no prison regulation or procedure laid down by prison regulation regulating the right to have interviews with the members of the family and friends can be upheld as constitutionally valid under Article 14 and 21, unless it is reasonable, fair and just.”

In Sunil Batra vs Delhi Administration too, the importance of family contact was highlighted. The court said that ‘subject to such considerations of security and discipline, liberal visits by family members, close friends and legitimate callers, are part of the prisoners’ kit of rights and shall be respected.’ Prisoners’ contact with family members is an indispensable right. This is even more important in the context of FNPs, as they can barely ever avail their right to mulaqaat.

While the Prisons Act, 1894, and the state jail manuals contain straightforward provisions to facilitate contact with family members for prisoners in general, the procedures for foreign nationals either do not exist or are Tedious. Similar to the restrictions on police, the prison departments are also unable to communicate directly with embassies without permission of the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) and state home departments.

Delhi Prisons – Circular dated 09/08/2016

Sub: Telephone facility to FNPs.

In continuation to the earlier standing Orders/Circulars issued, the competent Authority has considered the request of foreign national convicts with regard to make call to their country origin and has been pleased to accept their request with the directions that once a week the telephone facility should be extended to such prisoners. Each conversation will be held under the personal supervision of Dy. Supt./Asstt. Supdt. Designated by the concerned Superintendent of the Jail and the maximum duration of the conversation would be upto 10 minutes. The Superintendent Jail shall develop criteria for entertaining such requests and pass an order giving reasons in the event that such requests are not entertained. The Jail Superintendent will enter the details of the called numbers, the durations etc. for future references. The call made should be through speaker phone with a caller ID to ensure that the person called is the one in respect of whom the request is made by the prisoner. For keeping record of the call details it is suggested that a register should be maintained against the concerned in accordance with law.The facility can be withdrawn if any offence is committed by a prisoner during his stay inside the jail and/or if the telephone facility is found to be misused appropriate actions will be initiated against the concerned in accordance with law. This issues with the prior approval of the Competent Authority.

Barrier V: Lack of provisions to meet special needs

Obligation to afford a humane prison environment

Like all prisoners, foreign nationals must also be detained in humane conditions. However, issues such as language barriers, specific dietary requirements, cultural differences, and the lack of recreational or rehabilitative activities can often make it difficult for foreign prisoners to adapt to prison life.

Language: Language barriers are often responsible for FNPs’ sense of isolation. With absence of availability of prison rules in different languages, prisoners often do not understand their rights or obligations. Additionally, they may not be able to communicate with other prisoners or prison staff. Even simple things like making a request for medical assistance can go unheard if one cannot communicate in the local language. For example, a Bolivian lady was unable to explain her medical condition to the prison officials as she only spoke Spanish.

The prison authorities ultimately resorted to using web-based translation services to assist her.

Communication is key, but the difference in languages can lead to misunderstandings, which can in turn, attract or strengthen prejudices based on the colour of one’s skin or religion, etc. Other rights also get restricted due to the language struggle. An accused’s ability to understand court proceedings is an indispensable right to fair trial. The absence of good interpreters during the course of trial can render the prosecution and trial of a foreign prisoner futile. Linguistic difference can also lead to exclusion from different vocational and educational program. These can cause severe mental anguish to the prisoner.For example, a prisoner in Alwar Detention Centre (situated in the Alwar District Jail), who had been moved to detention after

completing his sentence in 2009, could hardly communicate, and was always found staring at the boundary wall. In the Rajasthan heat, he eventually suffered sunburns, but according to other inmates, continued sitting in the sun all day.

Information on processes: Lack of knowledge of the legal framework, legal procedures and lack of resources to hire services of competent lawyers further impacts the stay of FNPs in prison. Often, they are misled by lawyers and forced to plead guilty without understanding the consequences. Their lack of knowledge is further exploited when there is no consular access or contact with family members. Further securing bail is difficult and parole rules generally do not apply to them, this can inculcate anger within and leads to a tendency to resort to violence.

Diet, cultural differences and discrimination: The religious, dietary, spiritual or other specific needs of a foreign prisoner are very rarely addressed by the prison rules. ‘They are likely to have particular needs such as facilities for worship, special diets and hygiene requirements, due to their religion, which may be different to those of the majority prison population.’Diet patterns vary across states, thus restrictive diets, such as those which prohibit intake of meat can lead to discontentment in prisoners. Only few prisons provide special diets to foreigners,

which also may not suffice for all foreign nationals, given the diversity in dietary intake globally.

Barrier VI: Delay in nationality verification

Repatriation upon completion of sentence

The first step towards initiating the repatriation process is to verify the nationality of the person. For this, the prison departments write to the embassy of the country where the person is purported to belong. These requests are then routed through the prison headquarters, state home departments, ministry of external affairs before it reaches the embassy. This communication is required to contain all relevant details of the

prisoner, including copies of any identification documents he might possess. In absence of any identification documents, embassies are often reluctant to take any steps. However, in many cases, the identification documents are not available with the prisoner.

When a person gets arrested, he may be searched and his belongings may be seized by the police. In case of foreign nationals, these belongings also include their passports and other identification documents. These are then stored as evidence or seized items in the police malkhana, and remain there indefinitely.

For example, in the case of a Nigerian individual, the passport was traced to the police station 12 years after his arrest Similarly, in the case of a Palestinian person, it took almost a year to get a copy of the passport from the police station that was seized 23 years ago. Such issues result in inordinate delays in nationality verification with some embassies refusing to take any steps without a copy of the passport. Processes have to be initiated to procure the documents from the court or police malkhana.

However, this is not the only hindrance; in the absence of travel documents or identification records, it takes a long time for nationality to get verified by the consulate in question. They must also send the information to the respective government, which then initiates verification processes from their end. This too takes time.

For example, in the case of an alleged Sierra Leone national, it took almost a year for the embassy (which was located in China) to confirm that the person was not its national.

Barrier VII: Delay in obtaining Emergency Travel Certificate

Section 3 of the Passports Act, 1967, clearly specifies that ‘no person shall depart from, or attempt to depart from India unless he holds in this behalf a valid passport or travel document.’ Therefore, once the embassy verifies the nationality of the foreign prisoner, it must issue the person with an Emergency Travel Certificate (ETC) or a Travel Permit, which has the same value as that of a passport. This document permits the person to travel back to his country.

However, as explained above, this process can take time. An ETC is generally valid for a month, while a Travel Permit stays valid for 3 months, within which the outbound travel is to be made. Sometimes, there can be delays at the prison’s end or the foreigner regional registration office, or there can be a lack of funds due to which arrangements are not made for the travel. In such cases, the travel document has to be issued again, pushing back the process by a few more months.

Barrier VIII: Insufficient funds to support travel

Section 3(2)(cc) of the Foreigners Act 1946 requires foreigners to “meet from any resources at his disposal the cost of his removal from India”. Further, Para 14 of the Foreigners Order 1948 allows the Central Government to “apply any money or property of the foreigner in payment of the whole or any part of the expenses of or incidental to the voyage from India…until departure…” The law clearly places the responsibility of securing funds for travel on the prisoner, but in reality, this is difficult.

After long periods of incarceration, FNPs are left with little or no money. Sometimes, their travel may be sponsored by family members, but in a lot of cases, families too are incapable of offering funds. In some cases, embassies intervene to assist the process, but this is not a uniform practice. Countries with on- going humanitarian crises allocate budgets for voluntary repatriation of their nationals from other countries, which they often use to fund the deportation of their nationals as well (this is a practice in Afghanistan and Palestine).

Others contact the family of the prisoners or seek such funds from the prisoner. Sometimes, prison departments also concede to requests for sponsoring travel, but again, this is not a uniform practice.For the most part, expecting funds from FNPs is unrealistic since they are not allowed to work in detention.

Barrier IX: Logistical arrangements, approvals, etc.

Once the prison department receives the ETC and funds for travel are secured, there remain a number of processes to be completed before the repatriation.

This includes fixing the date of repatriation in consultation with the Foreigner Regional Registration Office (FRRO), issuance of deportation or removal order by FRRO, purchasing ticket for travel (in case of travel by air), requisition of escorts for transfer to the airport or integrated check post (ICP),securing approval from airlines or border security forces as the case may be, handing over belongings including valuable items and any wages earned to the person.

Once the process is completed, a report is sent from the prison to the prison headquarters and state home department. With no guidelines making the process timebound, there can be delays at every step of this process. In certain cases, where the prisoners’ families provide tickets, they might do it without consulting the FRRO.

It could be that during those days, escorts are not available or that the time for processing documents and receiving requisite approvals in insufficient. Thus, it is necessary to obtain consent from both FRRO and prison authorities before finalising the transfer date.

For example, a Bangladeshi prisoner could not be sent to the ICP because of lack of escorts. The same goes for the requirement for approval by airlines. To seek requisite permission, the following

documents should be made available: a copy of the deportation order, a risk-assessment report by the

state and/or any other pertinent information that would help the aircraft operator assess the risk to the security of the flights, and the names and nationalities of escorts.

After the FRRO representative or other competent authority on its behalf provides the copy of the ETC, deportation order, medical certificate and airline reservation, the airlines need atleast 10 days to provide clearance. However, there are often delays in receiving clearance, wherein clearance comes only 24- 36 hours prior to the flight, leaving the FRRO limited time to purchase tickets, coordinate with the jail and procure escorts.

There have also been instances where airlines refuse to allow boarding at the last moment leading to confusion, delay and loss of flight ticket money, adding to the woes of the prisoners. For example, a Palestinian prisoner could not board a flight as the airlines did not give clearance. He ended up being sent back to prison, pending his repatriation, which occurred after a month by another airline.

Nature of offences usually foreigners are charged with

Majority of the foreign inmates were charged with the offences under Passport (Entry into India) Act 1920 and Foreigners Act 1946. Most of the inmates of African origin were also charged under NDPS Act for smuggling of Narcotics drugs and the number of such inmates are increasing very rapidly. Some of the inmates were also charged under Explosives Substances Act whereas some were charged under the Official Secrets Act for spying. Most of the inmates (69 out of the total 88) made unauthorized entry into

Indian Territory whereas 19 came on valid visa but they were arrested because of expiry of visa or entering into undisclosed and unauthorized area.

Some inmates who made unauthorized entry into Indian Territory came in search of employment and got into the racket of drug trafficking and now are facing trails in Indian Courts under NDPS ACT and the numbers of such inmates are increasing very rapidly.

The Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985

Introduction: Overview

The Act is commonly known as NDPS Act and came into force on 14th November 1985. The narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances have medicinal and scientific value for which they have been used in India since decades. But with the passage of time and development, the practice turned into illicit drug trafficking. Also, India is signatory to UN Conventions on Narcotic Drugs which prescribes for the controlled and limited use of these narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances. Therefore, the legislation is framed with the objective of using these narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances in controlled manner for medicinal and scientific purpose without in contravention to the obligations to UN Conventions.

The NDPS Act regulates and controls the abuse of drug trafficking through its stringent provisions. It empowers the competent authority for the supervision of the operation related to narcotics drugs and psychotropic substances.

The NDPS Act prescribes stringent punishment. Hence a balance must be struck between the need of the law and the enforcement of such law on the one hand and the protection of citizens from oppression and injustice on the other. This would mean that a balance must be struck in. The provisions contained in Chapter V, intended for providing certain checks on exercise of powers of the authority concerned, are capable of being misused through

arbitrary or indiscriminate exercise unless strict compliance is required.

Critical analysis of Section 41, 42 and 50 of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act

Section 41: Power to issue warrant and authorization

This section can be divided into parts- first, power of issue of warrant and authorization to certain class of magistrate, gazetted officer and subordinate officers authorized by gazetted officers. Second, writing down the secret information.

It empowers a Metropolitan Magistrate or a magistrate of the first class or any Magistrate of the second class to issue a warrant for the arrest of any person whom they have reason to believe to have committed any offense punishable under the NDPS Act or for search of any building, conveyance or place in which they have reason to believe that any narcotic drug or psychotropic substance in respect of which an offence punishable under this Act has been committed, is kept or concealed.

It empowers gazetted officer of the department of central excise, narcotics, revenue intelligence or any department of Central Government including para- military forces or any department of State Government by special order of Central Government or in case of State by State Government if he has reason to believe from personal knowledge or information given by any person after writing down the information that any person has committed any offence punishable under this Act or any document or article

which may furnish evidences of the commission of any offence punishable under this Act.

The gazetted officer may authorize any officer subordinate (superior to rank of peon, constable or a sepoy) to conduct search, seizure of any building, conveyance and arrest of any such person whom he has reason to believe of commission of any offence punishable under this Act.

All Magistrates, empowered gazetted officers and authorized subordinate officers enjoy all the powers of an officer acting under Section 42 of the Act.

Section 42: Power of entry, search, seizure and arrest without warrant or authorization

This section can be divided into two parts:

First is the power of entry, search, seizure and arrest without warrant or authorization as contemplated under sub-section (1) of section 42. Second is reporting of information reduced to writing to the higher officer inconsonance with sub- section (2) of the Section.

Sub-section (1) of Section 42 lays down that the empowered officer, if has a prior information given by any person, should necessarily take it down in writing and where he has reason to believe from his personal knowledge that offences under Chapter IV have been committed or that materials which may furnish evidence of commission of such offences are concealed in any building etc. he may carry out the arrest or search, without

warrant between sunrise and sunset and he may do so after recording his reasons of belief.

The proviso to Sub-section (1) of Section 42 lays down that if the empowered officer has reason to believe that a search warrant or authorization cannot be obtained without affording opportunity for the concealment of evidence or facility for the escape of an offender, he may enter and search such building, conveyance or enclosed place, at any time between sunset and sunrise, after recording the grounds of his belief.

An officer writing down the information under sub- section (1) and an officer recording his reason of belief under proviso shall send a copy to their immediate superior officer.

Section 50:- Conditions under which search of persons shall be conducted.

Any Officer who is authorized to search under section 41, 42 and 43 shall without any delay take such person to the nearest magistrate or nearest gazetted officer of any departments of excise, customs, narcotics, revenue intelligence, or any other central or state department.

If the gazateed officer or magistrate cannot sees reasonable grounds for search then the person shall be released immediately otherwise should be directed to search. Female can only be searched by female. If in case it is not possible for officer to take person to nearest magistrate or gazateed officer then he can proceed search by himself under section 100 of Cr.P.C. But within 72 hours, officer has to write a reason of his belief of conducting research and send copy of it to immediate superior officer.

Section 52 Disposal of Persons Arrested and Articles Seized

- Any officer arresting a person under section 41, section 42 section 43 or section 44 shall, as soon as may be, inform him of the grounds for such arrest.

- Every person arrested and article seized under warrant issued under subsection (1) of section 41 shall be forwarded without unnecessary delay to the Magistrate by whom the warrant was issued.

- Every person arrested and article seized under sub-section (2) of section 41, section 42, section 43 or section 44 shall be forwarded without unnecessary delay to –

- The officer-in-charge of the nearest police station, or

- The officer empowered under section 53.

- The authority or officer to whom any person or article is forwarded under subsection(2) or sub-section (3) shall, with all convenient dispatch take such measures as may be necessary for the disposal according to law of such person or article.

Section 55 Police to Take Charge of Articles Seized and Delivered:

An officer-in-charge of a police station shall take charge of and keep in safe custody, pending the orders of the Magistrate, all articles seized under this Act within the local area of that police station and which may be delivered to him, and shall allow any officer who may accompany such articles to the police station or who may be deputed for the purpose, to affix his seal to such articles or to take samples of and from them and all samples so taken shall also be sealed with a seal of the officer-in-charge of the police station.

Section 57 Report of Arrest and Seizure

Whenever any person makes any arrest or seizure under this Act, he shall, within forty-eight hours next after such arrest or seizure, make a full report of all the particulars of such arrest of seizure to his immediate officer superior.

I. Guidelines for Investigating Officer issued by NICFS in

“A forensic guide for crime investigators”

The IO should ensure to follow the following guidelines and make notes in writing (ruqqa):

- Raiding party’s constitution, departure with/without vehicle, arms and ammunition, route taken, the name of the driver as well as accompanying of the informer.

- Numbers of independent public witness requested, their place, their background, i.e. whether they were passer- by, rickshaw pullers, residents, etc., and reasons for not joining.

- Time must be noted for important aspects like:

- Time of making DD entry

- Constitution of raiding part

- Time of leaving police station

- Time of arrival of spot

- Time of briefing to the team

- Time of nakabandi

- Time of apprehending of suspect

- Briefing of staff, area of nakabandi, how many parties put on nakabandi, who was standing where, position of the informer, etc.

- Time and direction of arrival of the suspect, whether he was carrying something with him, his turnout, etc.

- If anybody is accompanying the suspects, he must also be apprehended and interrogated thoroughly.

- If any vehicle is used, its number, make and colour.

- If the suspect spontaneously produces the contraband to the police, no need of notice u/s 50 NDPS Act.

- Complete description of packing/wrappers/marking and the contraband must be described in the writing (ruqqa) as well as in the seizure memo.

- The contraband must be checked through by field- testing kit.

- Sampling should be done properly. Two representative samples be taken.

- CFSL/FSL/CRCL form must be filled in instantaneously.

- Case property must be properly sealed with standard seal and the seal used must be handed over to any of the witnesses. While taking the case property in his charge, the SHO should counter-seal it with his own seal. Every addition in the FSL/CFSL/CRCL form, etc., must be duly signed by the SHO.

- If house search is to be conducted at night, reasons thereof must be recorded and sent to senior officers within 72 hours.

- Accused’s dossier must be prepared.

- First remand must be taken from the Magistrate concerned.

- In case, drug recovered is less than commercial quantity, the challan must be filed within 60 days whereas in case of commercial quantity, the challan may be filled in 90 days but the efforts should be to file the challan at the earliest.

- Sample must be sent to the laboratory for chemical analysis at the earliest. It should be in the knowledge of the SHO and covered in his statement.

- To maintain the sanctity of Diary Dispatch entries, they must be attested by a Gazetted Officer.

- Site plan must be described, prepared and elaborated and every minute detail of the scene should be mentioned in it.

- Previous involvements of the suspect in the drug trafficking, if any must be mentioned in the challan to enable the court for awarding enhanced punishment.

- Written work is done in the vehicle. If there is no vehicle, then the place where written work was done should be mentioned in the statements. Who arranged for the stool or chair is also be known to the IO/witnesses.

- A constable should not be allowed to make any search. It is prohibited in the NDPS Act.

- Parcels should be signed by the witnesses.

- The seizure should be weighed on the spot.

- Details of weighing balance, from where arranged, number of weights must be noted carefully.

- If vehicle is used, log book should be completed.

- Who did the written work, should be known to the witness.

- It should be mentioned in the writing (ruqqa) as to how many seals have been affixed.

- The SHO/Addl.SHO/IOs must get an official seal and at the time of raid, they should get the seal issued officially.

- There should be separate registers in the office of SHO, ACP and DCP in which date and time of dispatch and receipt of all reports should be mentioned.

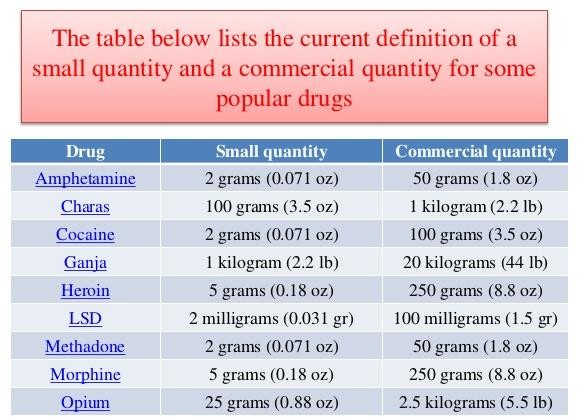

Small and Commercial Quantity of Important Drugs

According to Section 2 of NDPS Act:

‘Commercial quantity’, in relation to narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances, means any quantity greater than the quantity specified by the Central Government by notification in the official gazette.

‘Small quantity’, in relation to Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, means any quantity lesser than the quantity specified by the central government by notification in the Official Gazette.

Offences under commercial quantities are non-bailable U/S 37 NDPS Act 1985. However, if the court finds that the accused is not guilty of offence or is not likely to indulge in sale/ purchase of narcotic drugs, bail can be granted.

The punishment for many offences under Sections 15–23 of NDPS Act depends on the type and quantity of drugs involved—with three levels of punishments for small, lesser and immediate quantity, i.e. quantity more than small and lesser than commercial quantity.’

The punishment prescribed for different quantities is as follows:

- Where the contravention involves small quantity, with rigorous imprisonment for a term which may extend to six months, or with fine which may extend to Rs. 10,000 or with both.

- Where the contravention involves quantity lesser than commercial quantity but greater than small quantity, with rigorous imprisonment for a term which may extend to ten years and with fine which may extend to Rs. 1,00,000.

- Where the contravention involves commercial quantity, with rigorous imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than ten years but which may extend to twenty years and shall also be liable to fine which shall not be less than Rs. 1,00,000 but which may extend to Rs. 2,00,000.

Section 27 of NDPS Act: Punishment for Consumption of Any Narcotic Drug or Psychotropic Substance.

Whoever, consumes any narcotic drug or psychotropic substance shall be punishable,-

- where the narcotic drug or psychotropic substance consumed is cocaine, morphine, diacetyl-morphine or any other narcotic drug or any psychotropic substance as may be specified in this behalf by the central government by notification in the Official Gazette, with rigorous imprisonment for a term which may extend to one year, or with fine which may extend to Rs. 20,000; or with both.

- Where the narcotic drug or psychotropic substance consumed is other than those specified in or under clause (a), with imprisonment for a term which may extend to six months, or with fine which may extend to Rs. 10,000 or with both.

Section 31: Enhanced Punishment for Offences after Previous Conviction:

- If any person who has been convicted of the commission of, or attempt to commit, or abetment of, or criminal conspiracy to commit, any of the offences punishable under this Act is subsequently convicted of the commission of, or attempt to commit, or abetment of, or criminal conspiracy to commit, an offence punishable under this Act with the same amount of punishment shall be punished for the second and every subsequent offence with rigorous imprisonment for a term which may extend to onehalf of the maximum term of imprisonment and also be liable to fine which shall extend to one-half of the maximum amount of fine.

- Where the person referred to in sub-section (1) is liable to be punished with a minimum term of imprisonment and to a minimum amount of fine, the minimum punishment for such person shall be one-half of the minimum term of imprisonment and one-half of the minimum amounts of fine.

- Provided that the court may, for reasons to be recorded in the judgment, impose a fine exceeding the fine for which a person is liable.

- Where any person is convicted by a competent court of criminal jurisdiction outside India under any corresponding law, such person, with respect of such conviction, shall be dealt with for the purposes of sub-sections (1) and (2) as if he had been convicted by a court in India.

Starting of a Trail in Court

In a NDPS case, the investigation agency files the chargesheet of the case in the trail court. In a case where investigating agency is Narcotics Control Bureau, then instead of chargesheet a complaint is filed by IO in the trail court through Special Public Prosecutor.

A charge sheet is a final report prepared by the investigation or law enforcement agencies for proving the accusation of a crime in a criminal court of law. The report is basically submitted by the police officer in order to prove that the accused is connected with any offence or has committed any offence punishable under any penal statute having effect in India. The report entails and embodies all the stringent records right from the commencement of investigation procedure of lodging an FIR to till the completion of investigation and preparation of final report (Section 173(2) (i) and Section 173(5) of the Cr. P.C.).

A defence lawyer should check in a chargsheet that whether the procedure under the NDPS Act has been followed by the investigation agency/NCB or not and if not then such could be grounds for discharge/bail or acquittal of the accused in a case.

Here are some points which should be checked in chargesheet

- Was the information recorded in writing by him? (If he has received some informationSection 42 (1) of the NDPS Act)

- Were his belief and the ground that search authorization cannot be obtained without affording opportunity for concealment of evidence or facility for escape of the offenders, recorded in writing by him? (If he is proceeding to search premises without search authorization between sunset to sunrise, Proviso to Section 42 (1) of the NDPS Act)

- Was a copy of the said documents as at 1 or 2, as applicable, sent to his official superior within 72 hours? (Section 42(2) of the NDPS Act)

- Were the copy of Search Authorization shown and signatures of two independent local witnesses and the owner/occupier available in the premises obtained at the time of search? (In case, the search of premises is carried out on the strength of a search authorization)

- Did the search team offer their own personal search by the owner/occupier of the premises before beginning the search of the premises?

- Was a written notice under section 50 of the NDPS Act served to the occupants of the premises or on the person who is intercepted at a public place (This is a must if a person is given a body search and is not necessary if only the premises is searched or if the bag, brief case, etc. in the possession of the person is only searched)? Was the response to such a notice recorded in writing?

- Was a lady officer present in the search team to ensure that a female has searched a female? (Section 50(4) of the NDPS Act)

- Was there sufficient reason to believe that the person about to be searched will part possessions of drug and other incriminating articles and, hence, could not be taken to senior officers, and if yes, whether it was recorded in writing? (The person about to be searched for suspected drugs and other incriminating articles can exercise his legal right to be searched before a Magistrate or a Gazetted Officer, as provided in Section 50(1) of the NDPS Act)

- Was the copy of the documents, as at serial No. 8, sent to his immediate superior within 72 hours? (Section 50(6) of the NDPS Act)

- Were all recovered suspect substances field tested with Drug Detection Kits/Precursor Testing Kits and the matching colour resulted to show presence of NDPS or CS (Control Substances) and was it all documented?

- Were all the recovered documents, articles or things scrutinized/examined to determine their relevance to the commission of offence and importance to the inquiries under the Act?

- Were all recovered and relevant items liable to seizure and confiscation entered carefully in an inventory and documented in the Panchnama?

- Were all the goods, documents, articles, things and assets found relevant to the commission of offence and subsequent investigations, recovered during search, seizure and the fact of seizure documented in the Panchnama?

Points to check in chargesheet at the time of drawal of the samples

- Was a set of two representative samples drawn from each package or lot (if bunching was made into lots of 40 in case of ganja and hashish and 10 in case of other drugs) of the suspects seized substances on the spot?

- Was it ensured that the representative samples are of specified weights? (24 g. each in case of opium, ganja and charas and 5 g. each in case of all others). Less than 5g. may also be sent.

- Were all the packages including the representative samples properly packed, marked and sealed?

- (For easy reference, the parent package or lot can be marked as P1 and L1 and the two sets of samples as SOI and SDI and so on. Samples should be kept in heat sealed plastic pouches which may be kept in paper envelopes before marking and sealing).

- Was Test Memo prepared in triplicate on the spot and the facsimile imprint of the seal, used in sealing the sample envelopes, affixed on the Test Memo?

- Was the Panchanama/seizure memo/mahazar drawn carefully on the spot, correctly indicating sequence of events including start and end time of the search proceeding?

- Was it ensured that the Panchanama and all the recovered/seizure documents/article/ things bears signature of the person whose premises was searched or from whom the recovery was made. Two independent witnesses, the IO and the lady officer are to be present if a lady was searched?

- Was a notice to examine the owner/occupants and recovery witnesses under Section 67 of the Act issued and their statements recorded by the IO?

A Defence lawyer can easily get his or her client bail or aquitted in NDPS if the followings points are kept in mind while studying the chargsheet:

- Check whether IO forget to send a copy of the reasons to immediate superior officer under section 42 (2) of the Act. It’s non-compliance is fatal to the prosecution.

- Check whether arresting agency gave option of being searched by Gazetted Officer/a Magistrate to the accused under section 50 of the Act. It’s non-compliance is fatal to the prosecution.

- Check whether information received about some narcotic drug/ psychotropic substance illegally kept/concealed was reduced in writing or not . A copy of information to superior officer. Non-compliance of section 42 is fatal for prosecution.

- Check whether the search of female offender was made by a female constable under section 50 (4) of the Act. Non-compliance is fatal to the prosecution.

- Check whether after withdrawal the samples were sealed or not.

- Check whether the seal was handed over to independent witness till the case property is sent for analysis.

- Check whether Seizure memo, arrest memo, spot memo, etc., has been attested by witnesses or not ?

- Check whether the grounds of arrest were disclosed to accused and his/her family members/friends.

- Check whether case property was be produced before the Magistrate for attestation for pre-trial disposal. The inventory must be prepared and photographs taken in compliance with Section 52A (2) of the Act.

- Check whether any independent witness was called to join in investigation or not.

- Check whether the chargsheet/ Challan was filed before the trail court within the time frame prescribed by law.

Procedure to be followed while preparing Seizure List

In many cases the investigating agency makes few mistakes while preparing the seizure list and the defence lawyer should be study the chargsheet very carefully and see whether the procedure of seizure list was followed or not and if not then that can be the ground for bail/acquittal in a NDPS case.

- Prepare list of evidence material collected from the scene.

- List should be signed by two public witnesses giving their full details including permanent and temporary addresses.

- The packets/parcels containing evidence material should be labelled giving description of its contents (exhibits), case reference and should be signed by the IO.

- Forwarding memo should be filled up giving brief history of the case, details of the parcels and their contents, nature of examination required and certificate authorizing the Director, Forensic Science Laboratory for examination of the exhibits.

BAIL

Law of Bail is very important in Criminal Law. Sometimes innocent persons are implicated and they have to remain in jail for a verylong time without any fault on their parts. This results in violation of their fundamental right of life and personal liberty enshrined in Article 21 of the Constitution. On the other hand, the social interest demands that the culprits should not be left free to indulge in further activities. Keeping the fact into consideration, special provisions of Bail have been made in NDPS Act, 1985.

Section 37 of NDPS Act

Special provision has been prescribed under section 37 of the Act while considering the bail matters of the accused persons. Section 37 of the Act is reproduced as under:

Section 37 of NDPS Act reads as under

Section 37:-Offences to be cognizable and non-bailable:-

- Notwithstanding anything contained in the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (2 of 1974),

- every offence punishable under this act shall be cognizable;

- no person accused of an offence punishable for [offences under section 19 or section 24 or section 27 A and also for offences involving commercial quantity ] shall be released on bail or on his own bond unless).the Public Prosecutor has been given an opportunity to oppose the application for such release, and

ii) where the Public Prosecutor opposes the application the court is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for believing that he is not guilty of such offence and that he is not likely to commit any offence while on bail.

- The limitations on granting of bail specified in clause (b) of subsection (1) are in addition to the limitation under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (2 of 1974) or any other law for the time being in force on granting of bail. Certain changes have been made in this section under amendment Act 2001.

The Law of Bails which constitutes an important branch of the procedural law has to dovetail two conflicting demands namely, on one hand, the requirements of the society for being shielded from the hazards of being exposed to the misadventures of a person alleged to have committed a crime, and on the other hand, the fundamental canon of criminal jurisprudence viz, the presumption of innocence of an accused till he is found guilty. Personal liberty is a constitutionally protected right. Being Constitutional right no one can deprive personal liberty of a citizen so easily.

But on the other hand the drugs evil is also of national and international importance. So, in between these two rivals one overrides the other in the existing national or international scenario. If there exists prima facie case that accused has committed offence in that station at any cost no bail is to be granted to the accused. Liberty of citizens has to be balanced specifically mentioned in section 37 (1) (b) his bail petition would be disposed off with reference to the general provisions of bail contained in the Cr. P. C. and not with reference to the limitations specified in section 37 of NDPS Act. This is a very healthy change.

But now after the enforcement of the said amendment Act No. 9 of 2001 the words “ a term of imprisonment of five years or more are being substituted by the words” offences under section 19 or section 24 or section 27A and also for offences involving commercial quantity. After the said substitution of words the special procedure for bail contained in section 37 of the NDPS Act would apply only to a person accused of an offence punishable for offences under section 19 or 24 or section 27A and also for offences involving commercial quantity.

In view of the recent amendments of the NDPS Act by the NDPS Amendment Act (Act 9 of 2001), 2001 and following the decision of the Supreme Court (i) Rajiv Chaudhary v. State of Delhi1 and Chandan Das v. The State the prescribed period of detention for an offence involving quantity less than ‘commercial quantity’ but more than ‘small quantity’ is 60 days as provided under Section 167 (2) Cr.P.C. because the sentence provided in such cases is not more than 10 years imprisonment with the interest of the society. The change effected through Act No.9 of 2001 would be very vital. The amended provisions have liberalized bail provisions in respect of certain offences. It may be stated here, that on enforcement of the provisions of Act No. 9 an accused of an offence punishable for offences U/S 19 or Sec. 24 or Sec. 27- A and also for offences involving commercial quantity would not be granted bail under the provisions contained in the chapter xxxiii of the code of Cr. P. C. special provision of bail inserted in sec. 37 would apply in such cases. The net result of the amendments made in sec. 37 of NDPS Act now, onward, would be that except in cases wherein an accused is charged for an offence.

(ii) Arif Khan @ Agha Khan vs The State Of Uttarakhand on 27 April, 2018, Learned counsel contended that the prosecution has failed to ensure mandatory compliance of Section 50 of the NDPS Act inasmuch as the alleged recovery/search of the contraband (Charas) made by the raiding police party from the appellant’s body was not done in accordance with the procedure prescribed under Section 50 of the NDPS Act which according to learned counsel is mandatory as held by this Court in the case of Vijaysinh Chandubha Jadeja vs. State of Gujarat, 2011(1) SCC 609. The short question which arises for consideration in the appeal is whether the search/recovery made by the police officials from the appellant (accused) of the alleged contraband (charas) can be held to be in accordance with the procedure prescribed under Section 50 of the NDPS Act. For the aforementioned reasons, we are of the considered opinion that the prosecution was not able to prove that the search and recovery of the contraband (Charas) made from the appellant was in accordance with the procedure prescribed under Section 50 of the NDPS Act. Since the non-compliance of the mandatory procedure prescribed under Section 50 of the NDPS Act is fatal to the prosecution case and, in this case, we have found that the prosecution has failed to prove the compliance as required in law, the appellant is entitled to claim its benefit to seek his acquittal.

(iii) Vijaysinh Chandubha Jadeja vs State Of Gujarat on 29 October, 2010.In view of the foregoing discussion, we are of the firm opinion that the object with which right under Section 50(1) of the NDPS Act, by way of a safeguard, has been conferred on the suspect, viz. to check the misuse of power, to avoid harm to innocent persons and to minimise the allegations of planting or foisting of false cases by the law enforcement agencies, it would be imperative on the part of the empowered officer to apprise the person intended to be searched of his right to be searched before a gazetted officer or a Magistrate. We have no hesitation in holding that in so far as the obligation of the authorised officer under sub-section (1) of Section 50 of the NDPS Act is concerned, it is mandatory and requires a strict compliance. Failure to comply with the provision would render the recovery of the illicit article suspect and vitiate the conviction if the same is recorded only on the basis of the recovery of the illicit article from the person of the accused during such search. Thereafter, the suspect may or may not choose to exercise the right provided to him under the said provision. As observed in Re Presidential Poll14, it is the duty of the courts to get at the real intention of the Legislature by carefully attending to the whole scope of the provision to be construed. “The key to the opening of every law is the reason and spirit of the law, it is the animus imponentis, the intention of the law maker expressed in the law itself, taken as a whole.” We are of the opinion that the concept of “substantial compliance” with the requirement of Section 50 of the NDPS Act introduced and read into the mandate of the said Section in Joseph Fernandez (supra) and Prabha Shankar Dubey (supra) is neither borne out from the language of sub-section (1) of Section 50 nor it is in consonance with the dictum laid down in Baldev Singh’s case (supra). Needless to add that the question whether or not the procedure prescribed has been followed and the requirement of Section 50 had been met, is a matter of trial. It would neither be possible nor feasible to lay down any absolute formula in that behalf. We also feel that though Section 50 gives an option to the empowered officer to take such person (suspect) either before the nearest gazetted officer or the Magistrate but in order to impart authenticity, transparency and creditworthiness to the entire proceedings, in the first instance, an endeavour should be to produce the suspect before the nearest Magistrate, who enjoys more confidence of (1974) 2 SCC 33 the common man compared to any other officer. It would not only add legitimacy to the search proceedings, it may verily strengthen the prosecution as well.

(iv) The State Of Punjab vs Baljinder Singh on 15 October, 2019 Since in the present matter, seven bags of poppy husk each weighing 34 kgs. were found from the vehicle which was being driven by accused- Baljinder Singh with the other accused accompanying him, their presence and possession of the contraband material stood completely established. 20. In the circumstances, the acquittal recorded by the High Court, in our considered view, was not correct. We, therefore, set aside the view taken by the High Court. While allowing this appeal, we restore the order of conviction recorded by the Trial Court and hold accused Baljinder Singh and Khushi Khan to be guilty of the offence punishable under Section 50 of the Act. We, however, reduce their substantive sentence from 12 years to 10 years while maintaining other incidents of sentence namely, the payment of fine and the default sentence unaltered. The appeals stand allowed in aforesaid terms. 21. Both the accused are given time till 15 th November, 2019 to surrender before the concerned police station to undergo remaining sentence. In case, the accused fail to surrender within said period, they shall immediately be taken into custody by the concerned Police Station. A copy of this judgment shall be communicated to the concerned Chief Judicial Magistrate and Police Station for compliance. The compliance in that behalf shall be reported to this Court on or before 01.12.2019

(v) Joginder Singh vs State Of Punjab on 28 May, 2019 Vide this common order, I dispose of all the aforementioned petitions, as it is noticed in many cases that the Investigating Officers, while conducting the investigation under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 (for short ‘NDPS Act’), are not adhering to the mandatory provisions of NDPS Act. Though it cannot be said at this stage whether the Investigating Officers are leaving a lacuna intentionally to do favour to the accused persons, as on the other hand, a common defence is taken by all the accused persons that they have been falsely implicated yet the lapses on the part of Investigating Officers need to be checked in future. Since the petitioners, in all these cases, were granted interim bail vide orders by this Court, finding the lacunae in the investigation, the interim 18 of 19 CRM-M-5074-2019 and other cases -19- bail granted to them is made absolute

You may contact me for consultation or advice by visiting Contact Us

you make it seem so effortless but I know you must have worked hard on this

This article is very informative